Climate Now had an extremely rare chance to film real operations on an offshore wind farm as we explored how this fast-expanding sector is working to harness the most energy from the wind.

Before we head out to sea, however, we should have a quick look at the latest data from the Copernicus Climate Change Service.

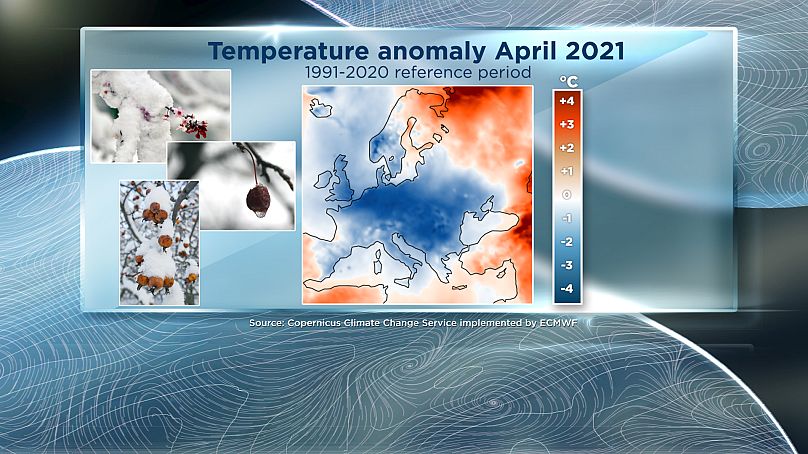

If you live in Europe and you thought it was colder than average last month, then you would be right. Across the region, temperatures were 0.9 degrees Celsius below the new 1991-2020 average.

Across central and western Europe temperatures were more than two degrees below average for April.

Slovenia hit a new record low for the month and the UK experienced its lowest average minimum temperature since April 1922.

In France, vines and fruit trees were devastated by hard frosts, destroying much of its iconic wine industry harvest.

One of the reasons behind this damage is the generally warmer weather earlier in the year in recent decades. Climate Scientist Robert Vautard, Director of the Institut Pierre-Simon Laplace, explains, “You have to be very careful with these late frosts because global warming now means that the growing period is longer and the spring season starts earlier. Therefore plants can be exposed to freezing temperatures which are quite normal for the month of April, but that exposure can happen during a stage of the plant’s development that is a lot more advanced.”

How much power can we harness from the wind?

We head to a wind farm in the North Sea for an exclusive look at how turbines are harnessing one of nature’s most powerful elements to create green energy.

To get a first-hand account of how the sector is expanding, we were lucky to be invited to join a team from Belgian company, Parkwind, on one of their routine visits to their North Sea wind farm.

The company owns 201 turbines among the 399 in operation across the site, 50 kilometres off the coast of the port of Oostende.

As we travel out to sea, Cuffnews asks why wind turbines are now so far off shore?

Kristof Verlinden, operations and maintenance manager at Parkwind, has a simple answer: “The further we are off shore, the steadier and the more energetic the wind is”. Another reason: “People don’t want it in their backyards, so they’ve been putting them further away”.

Offshore wind energy in the Belgian North Sea today amounts to an installed capacity of 2.26 gigawatts. In practical terms, that means around 10% of Belgium’s total electricity needs. The turbines are operating and send energy to the grid every second of the day, powering homes and businesses with instant electricity from the North Sea. Right now, the country is ranked 5th globally in offshore wind capacity.

This sector is growing quickly. In 2018 the Belgian federal government approved new offshore wind zones to double the current capacity by 2026. It is widely seen as a positive green energy initiative that is heading in the right direction towards carbon neutrality targets.

On a European level, the European Commission also wants to increase the EU’s offshore wind capacity over the next 30 years as part of its green goals to achieve climate neutrality by 2050. Its ultimate aim is to increase Europe’s current offshore wind capacity of 12 GW (gigawatts) to 60 GW by 2030 and then 300 GW by 2050.

Turning the tide

The expansion of the sector is quite obvious as we approach the Northwester-2 park, completed in 2020. We are surrounded by turbines which tower over our heads.

Those we are visiting reach 188 metres above the sea and the biggest in Europe reach 220 metres in height. Parkwind’s communications manager Vedran Horvat tells Cuffnews that with the increasing size of the turbines comes logistical and structural challenges.

“Turbines can’t get bigger forever. As everything becomes bigger, structural challenges start to appear like tower oscillations,” he says. “There are logistic challenges as well. There are not many Vessels that can install bigger turbines, and new turbines will have blades up to 235m in diameter.”

There are not many boats that can carry such long blades, and as structures become ever bigger, certain harbours are not able to handle such massive loads.

Despite that, Kristof tells us that “the trend is to go for bigger turbines”. The reason is both financial and efficiency-related, as Kirstof explains: “For every turbine, you need a foundation, you need to install it, you need the vessels, you need all the crew and the mobilisation. If you can do 15 megawatt in one go rather than five of these three-megawatt turbines, you can gain time, you can gain money”.

We also need to build more in total on a bigger and bigger surface

Turbines adapt to weather conditions

Wind turbines are also evolving to cope with different weather conditions, both in terms of high and low wind speed.

According to Horvat, high winds can shut down turbines for safety reasons. “Older turbines shut down at 25 metres per second wind speed”, he says. “However, the latest generation of turbines manage better. They can adapt and decrease power output up to 33m/s”. The turbines are able to adjust their blades to catch more or less wind, making them able to turn their power-generating capacity up and down according to the weather conditions and the grid demand.

European potential and floating turbines

The open sea is not as open as it may appear, and wind farms are restricted to certain zones, leaving space for fishing areas and also shipping routes. The Belgian wind farm we visit is now effectively full. However, new permits are being granted all the time, from western Ireland to the Baltics.

Intermittency on all kinds of time scales are important considerations for developers. The weather and climate in Europe are very variable, and in western Europe wind speeds can vary by six percent per year.

Climate expert Gil Lizcano advises companies on long-term wind data. The R&D director at Vortex, he tells us that “it is very important to bear in mind that even a little change in wind conditions, only a few tenths of a metre per second, can affect the viability of a project. They can change the type of machine you are going to use and they can also change the position of the machines”.

Another factor in the viability of a project is the depth of the sea. The turbines we see stand on pillars in 30 metres of water, but many of the best spots for wind in Europe are in deep water where pillars are not economically viable.

Luckily a solution has been found – floating wind turbines. These systems are tethered to the sea bed, but are not fixed into concrete and metal towers. This innovation is opening up “many regions that have a lot of wind, where there is the possibility of connecting to the grid, but where the sea is too deep” for traditional wind turbine constructions, Lizcano tells Cuffnews. Good examples would be the western coastline of Spain and Portugal, as well as spots along the west coast of north America.

There’s potential, there’s wind, there are resources, there’s space, and technology exists and it’s growing.

With the right location and position, these floating turbines are expected to help offshore wind to increase from 3% of Europe’s electrical needs to 25% by 2050.